Mandela entered office as South Africa’s first black president resolute to unite his divided people into the rainbow nation that Nobel Peace laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu had been preaching about for years. As optimism swept through the nation, it seemed that South Africa would be an example of reconciliation and non-racialism to the world.

The optimism however began to fade when Mandela’s successor, President Thabo Mbeki, resigned in September 2008 at the behest of the African National Congress (ANC) after Jacob Zuma had ousted him as the liberation movement’s president.

Zuma’s ascendency was open sesame for the forces of looting, which were allegedly orchestrated by the three infamous Indian Gupta brothers, who have since fled the country. In a frenzy called “state capture”, they voraciously fed on state-owned companies. However, capturing President Zuma and making him their pliant politician who colluded with them before making Cabinet appointments, was their biggest coup. They also looted previously strong and respected state-owned entities such as energy generator Eskom, and the railway entity Transnet.

According to evidence presented to the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, also known as the Zondo Commission, a 2018 public enquiry tasked with investigating state capture, the Guptas allegedly looted almost US $1 billion, while the overall state capture amount was over US $3 billion.

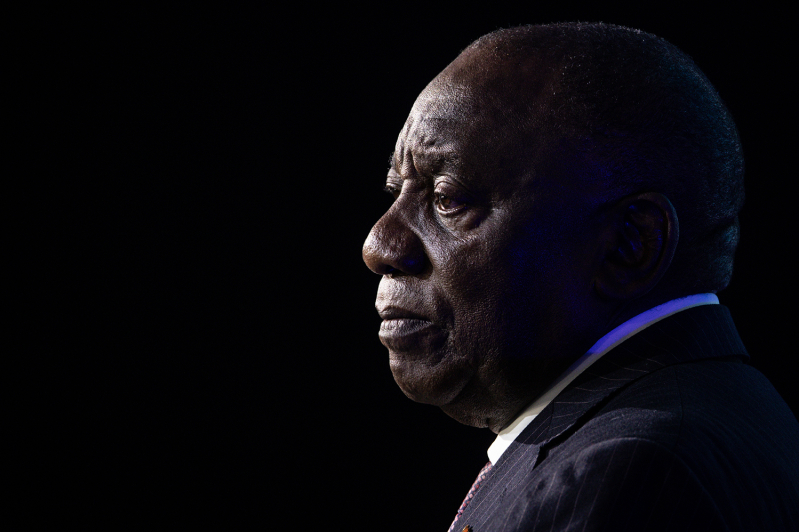

While he was not party to this devastating looting of South Africa’s resources, Cyril Ramaphosa was Jacob Zuma’s Deputy President from 2009 until his ousting in 2018 when he replaced him as head of state.

President Ramaphosa has referred to Zuma’s tenure as “the nine lost years”. However, he cannot sidestep responsibility. As Deputy President, he played an important role in the era of state capture, the Africanisation of governance and the walk-away from Mandela’s vision of non-racialism, the introduction of electricity shortages known as loadshedding, failure of the ANC government to render basic services and the resultant huge loss of confidence in the ANC.

The diminished faith in the ANC was profoundly mirrored in the black community and was responsible for the party losing its parliamentary majority for the first time since 1994 when South Africans voted on May 29 this year. The ANC slumped from 230 seats after the 2019 election to 159 seats, while the Democratic Alliance (DA) got 87, Zuma’s new uMkhonto weSizwe Party (MKP) 58, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) 39, and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) 17.

The ruling party’s defeat in the May general election and the success of the MK Party, the product of a breakaway from the ANC that Zuma had launched in the Zulu majority province of KwaZulu-Natal, humbled the ANC. It was forced to take a hard look at itself, the options available to it, the suitability of would-be alliance partners and – if one can believe it, given its record of misgovernance – what would be the best for South Africa.

What emerged was a party that was not its usual arrogant self, but a friendlier and more reconciliatory one which talked of forming a Government of National Unity (GNU) with opposition parties, including the DA, a party that it usually condemns as being anti-poor, pro-capital, pro-white, reactionary and of longing to bring back racial segregation. In advocating a unity government, the ANC was pushing both the DA and the reactionary and leftist EFF into a corner. The DA had to consider going into an alliance with the ANC instead of remaining an opposition party.

Led by firebrand Julius Malema the EFF had built a reputation for bringing chaos to the South African parliament. Malema, filled with self-importance, was seeing himself as being sworn in as the next president after the elections. Like the ANC, he too was brought down to earth.

The EFF flatly refused to join a Government of National Unity that would include what they deem the enemy, the DA, while the latter despite its anti-ANC rhetoric was more pragmatic and decided to join the GNU. The IFP, a mostly Zulu party, also allied itself with the ANC and DA. Together they and a few other smaller parties voted in Cyril Ramaphosa as President for a second term on June 14. In a historic sitting, the DA’s Annelie Lotriet was elected Deputy Speaker of Parliament.

She is the first white person, as well as the first opposition politician, to fill this position. But then this is a new era of a politics in South Africa, an era in which the ANC’s divisive politics will have to make way for a more inclusive country trying to pursue the non-racial dreams of Nelson Mandela and the 1976 generation of the Soweto uprising.

Of course in South Africa, politics would not be normal if there was not a group of spoilers occupying one side of parliament. Jacob Zuma has failed to use the courts to overturn the election results. This has not stopped the infamous octogenarian, who the South African Constitutional Court has unanimously ruled cannot go to parliament because he has a criminal record, from sniping at the Government of National Unity, calling it a white-led unholy alliance that is being sponsored by big business and which is a deal made for the markets and not the people.

His MK Party, which has wiped the floor with the ANC in KwaZulu-Natal, has joined a group of six other parties that have banded together under the name Progressive Caucus. Their performance in parliament is likely to be anything but progressive and possibly rather disruptive. They are also likely to stir up angry and resentful sentiments outside parliament.

President Ramaphosa’s insipid leadership of the ANC and South Africa during his first tenure as President makes him vulnerable to a leadership challenge in his own party where the less pragmatic and disgruntled alliance partners, the South African Communist Party and Congress of South African Trade Union are virulently against the new governing coalition with the DA.

At his inauguration at the Union Buildings in Pretoria on Wednesday (19 June) President Ramaphosa said that the outcome of the election had pushed South Africa to a point where it had to choose to move forward together or risk losing everything it had built in the last 30 years.

He said: “This moment requires extraordinary courage and leadership. It requires a common mission to safeguard national unity, peace, stability, inclusive economic growth, non-racialism and non-sexism.”

He added that through their ballots, South Africans made it plain that their expectations were that the leaders of the country should work together. “They have directed their representatives to put aside their animosity and dissent, to abandon narrow interests, and to pursue together only that which benefits the nation.”

Solemnly he pronounced that parties in the Government of National Unity were called upon to partner towards a growing economy, better jobs, safer communities, and a government that would work for all its people.

“The formation of a Government of National Unity is a moment of profound significance. It is the beginning of a new era,” he said.

President Ramaphosa and the ANC are unfortunately rich in promises, yet very poor when it comes to delivery. Perhaps his new governing alliance partners will shake him up but his record of underperforming and not fulfilling all of his grandiose pledges does not inspire confidence.

An indicator of how serious and committed he is will be reflected by his Cabinet appointments and whether the ANC is really willing to share power and face up to the Progressive Caucus in the opposition benches. There is hope for South Africa if they are. If not, the new era that Ramaphosa talks about will be nothing more than a lofty ideal falling to the ground and quickly evaporating in the hot African sun, just like the “new dawn” that he declared when he first became President in February 2018.

South Africans are probably headed for a rocky, uncomfortable ride, because there are many who continue to reject Mandela’s vision of a united, non-racial democracy. However, it is a vision that has inspired post-apartheid South Africa and should be harnessed again for the sake of this beautiful troubled country and its people.

Dennis Cruywagen is an acclaimed South African journalist and political commentator, as well as a former parliamentary spokesperson for the ANC. He previously served as deputy editor of the Pretoria News and a political reporter on the Cape Argus. He is a recipient of a Nieman Fellowship and a Mason Fellowship at Harvard University, and holds a master's degree from Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. He is also the author of Brothers in War and Peace and The Spiritual Mandela: Faith and Religion in the Life of Nelson Mandela.