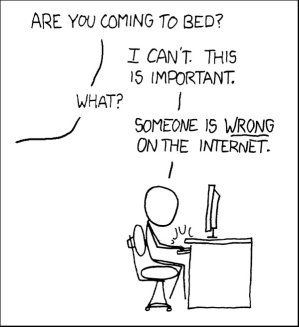

Aren’t you just furious when someone on the internet is wrong? When someone spouts their opinion and you know far better than them that what they are saying is ill informed nonsense?

This is a precarious topic for me to brooch, because I have certainly found myself on both sides of this scenario—both wanting to respond to others, but also putting my views out their and getting somewhat robust feedback.

It’s also close to home as public political communication is part of my job.

Platforms, opinions, and spin

The role of the political commentator, or political pundit, is one that has grown over the years and exponentially so with social media. The middle pages of newspapers used to include comment pieces from named authors and leader articles representing the paper’s position.

There was a narrow space in some news discussion shows for discussion and comment on the news, and then 24 hour news programming blurred the lines between comment and news to fill the hours. Experts were invited on current affairs shows to talk about what is happening with particular insight.

Radio, especially talk-back radio, was a place where more opinionated discussion found a home, shock jock hosts outraging and enthralling listeners as they baited them with provocative thoughts and views.

But now everyone has a platform. And sometimes it seems like everyone feels like they need to use it.

The other evolution that has changed our engagement with news is the democratization of what is commonly known as spin.

The study of history is not really about the recollection of facts but about how they are interpreted and understood.

I remember a day early in my senior high school history course when I was introduced to the concept of historiography—that the study of history is not really about the recollection of facts but about how they are interpreted and understood. The idiom that victors write the history books has often been true, and much of recent historical study has been about trying to reassess our understanding of events without the distortion of that lens.

Former British journalist and political opinion influencer, Alistair Campbell was not the first so-called "spin doctor", but he’s certainly the person who popularized the concept. Political communication is not neutral.

What is talked about and how it is talked about affects our understanding of events. Putting a positive spin on events becomes enmeshed with distortion and deceit. We need to ask, when is prioritizing certain pieces of information hiding others? When does releasing unwelcome statistics on a day where attention is elsewhere considered to be "burying bad news".

Communication is not neutral.

All this to say that communication is not neutral. How we talk about events, and what we choose to talk about conveys what we think is important and what we want people to know about.

It is frequently remarked that the news is not balanced. Why does one scandal get days of coverage while another drifts off after a minor story on the online equivalent of page 33? Why does one murder spark politicians pledging changes to laws, while another doesn’t even make the local news? Why is a hurricane in Tennessee covered in UK media but an earthquake in Nepal ignored?

Christians as social and political commentators

What place is there for Christian commentators?

This all leads me to wonder what place is there for Christian commentators, and brings me to the point of this opinion piece: what role should Christians play in commenting on news events? Knowing that in doing so we are not neutral either.

The case for the defense: someone is commenting on events so it is important, nay, vital, that Christians are involved in providing Spirit-filled, biblically informed, wisdom to current affairs.

The case for the prosecution: Christians add to the noise and confusion. Christians are as likely to bring their political and ideological opinions, their prejudices and blind spots, to political debate and masquerade those things as biblical wisdom.

Of course these are extreme positions, but the arguments in favor or against would lean in either one of these directions. The inevitable response is that it depends who is doing the commentating and how they are doing it. So, what follows is an attempt to find redemptive elements to the most flawed efforts at commentary, and then look at the risks even when it is done exceptionally well.

We all come to issues with our own prejudices and blind spots.

We all come to issues with our own prejudices and blind spots—no one is exempt from this. The healthiest way to find out these is to engage in debate and discussion. It exposes us to alternative viewpoints and this knocks off the edges of our thinking as we consider perspectives we might not have encountered if we kept our thoughts to ourselves.

If we waited for the perfect person to make the perfect argument, we would be waiting a very long time. Rather, we should engage charitably with those we disagree with, and from the perspective of a commentator I think an element of humility is essential. We might hold views very strongly, but we might still be wrong—however unlikely we think that might be!

Furthermore, people have different views, we legitimately think differently about things. Take much of politics, for example. As Christians we might agree with an overall policy objective, say, reducing poverty, but fundamentally disagree on how to achieve that. In many areas, once we get into practical details of how to achieve something there will be far less clarity about the specifics as regards how we should think about an issue as Christians.

It is helpful to think deeply about positions, policies, and practicalities.

It is helpful to think deeply about positions, policies, and practicalities—often there will be common ground for Christians on positions, but as we move through policies and into practicalities there will be increasing divergence.

This helpfully leads us to some of the risks even when commentary is done well. When we are engaging at the level of policies and practicalities there is the risk of implying that people who disagree with our particular solution also disagree with our position. They might, but sometimes we feed disagreement back up the chain of reasoning when that is not necessarily inevitable.

Who are you speaking for?

Another risk that is ever present is over correction. This is where we respond with equal vociferance (shouting) when someone has said something in strident terms that we disagree with. Online spaces are particularly notable for this—with strongly held and strongly worded opinions validated by clicks and views that can serve to escalate the debate.

The final risk is the question of whom are you speaking for? This is personal. When I post online I risk people assuming that I am speaking for the Evangelical Alliance. A couple of times I’ve posted something on X (formerly known as Twitter) only to find it reported in a news piece as a comment from the UK Evangelical Alliance! In neither case I can recall was it problematic, but demonstrates the challenge. For people with organization roles it can be assumed—regardless of any caveats in your bio—that your views represent that organization.

There can be consensus about the broad position Christians should take but deep disagreement as to the specifics.

For me, this means I have to be careful what I comment on, as I know there are issues where the Evangelical Alliance won’t take a public position. Many policy areas relating to economics come into this category for the reason noted above, there can be consensus about the broad position Christians should take but deep disagreement as to the specifics.

The other side of this is that some who speak are just speaking for themselves, but their views and opinions might be reported or viewed as representing Christians more generally, and this is an impossibly gray area. The spectrum between saying Christians think Jesus rose from the dead, and Christians support unhindered gun ownership rights, is vast. And along that spectrum are many points of nuance, where views may be held by many but not universally.

Let's take a present topic as a concrete example: it would be incorrect to say or infer that all Christians oppose efforts to introduce assisted suicide. I would argue they should, but they don’t. And if I were to speak on this I could do so confidently because the Evangelical Alliance has a clear position of opposition. I would fairly represent my organization's view, but would not necessarily speak for the entire Christian population.

The burden of representing a diverse constituency can sometimes hinder a position being made public in a timely manner because of the need to seek a collectively and expertly formed consensus. Whereas, the immediacy of social media favors the lone wolf who has no accountability for what they say. Lone commentators are free to speak boldly, which can have value and cut through into public awareness when done well, but it also carries significant risks—particularly if they presume to represent a broad consensus when in fact they don't.

Silence isn’t an option for many issues.

All the pros and cons considered, my final comment is that silence isn’t an option for many issues. Silence suggests that we don’t care, or that we have nothing to say. The challenge then is to speak with clarity and well-reasoned conviction—with wisdom, grace and humility.

Originally published by Danny's Substack. Republished with permission.

Danny Webster leads the Evangelical Alliance UK's advocacy team, including public policy work, engagement with parliaments and assemblies, and respective governments. He has degrees in politics and political philosophy and worked in parliament for an MP. Danny is passionate about encouraging Christians to integrate their faith with all areas of their life, especially when it comes to helping them take on leadership outside the church, and helped initiate the Evangelical Alliance's Public Leadership program. He is a baker, house renovator, occasionally funny, rarely profound, and tweets all his own work (on X, formally known as Twitter). Danny hosts a Substack at: https://dannypwebster.substack.com.