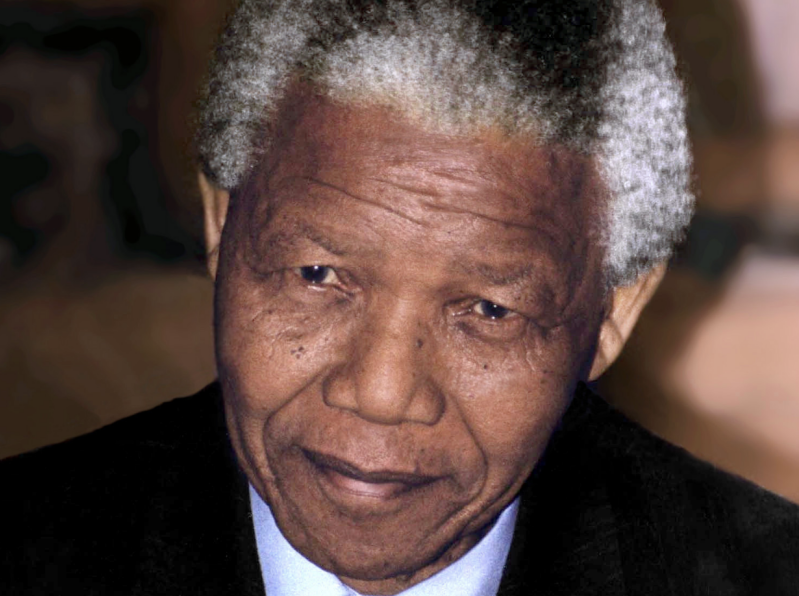

Thirty years ago, Nelson Mandela, who spent 27 years as a political prisoner, took the oath of office at the Union Buildings in Pretoria – an act that declared to his country and the world that white minority rule had ended in South Africa.

On that autumn Tuesday, all South Africans were finally free and equal before the law. Apartheid was over, the transition to democracy was peaceful, and now we could boldly look at the future. As our vibrant new multi-coloured flag flew for the first time, we were proud to be South African and to support Mandela in his vision of reshaping a formerly pariah state into a united, non-racial country.

This humble, tall man whom history had anointed to epitomise forgiveness, reconciliation, love for his country and its people, gave us his infectious optimism. South Africans believed and trusted Mandela because he had the courage and moral fibre to lead us into the unknown.

However, none of the men who followed him into the Presidency have come close to enjoying the adulation and respect that Mandela commanded. With Mandela at the helm, it felt that South Africa could not put a foot wrong.

Although the country would have applauded and supported him to serve another term, Mandela announced he would not be seeking re-election in 1999. At age 81, he stepped down to make way for Thabo Mbeki to become South Africa’s second democratically elected President. Not nearly as enthusiastic as Mandela, Mbeki did distinguish himself with policies that continued to rebuild the economy, a sharp intelligence, honesty and dedication to South Africa.

His HIV/AIDS policies, however, were tragic. A doctoral thesis at the Harvard School of Public Health said that between 2000 and 2005 an estimated 330,000 people died in South Africa from HIV/AIDS because of the Mbeki government’s obstruction of life-saving treatment. In the same period at least 35,000 babies were born with HIV infections. Mandela was deeply critical of Mbeki’s HIV/AIDS policies and did not mask his disapproval.

Despite this tension, Mbeki was respected in his country. Yet critics, such as the Africa National Congress’ (ANC) allies the South African Communist Party (SACP) and Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), condemned him for being aloof, and of not pursuing policies of which they approved.

As president of the ANC, Mbeki was in total control of the liberation movement. However, he was not untouchable. In June 2005, he rose in Parliament to announce: “I have come to the conclusion that the circumstances dictate that in the interest of the honourable deputy president, the government, our young democratic system and our country, it would be best to release the honorable Jacob Zuma from his responsibilities as deputy president of the republic and member of the cabinet.”

In hindsight, that dramatic moment was the beginning of the end for Mbeki. It gave Zuma space to portray himself as a victim, mobilise against Mbeki, and get the SACP and COSATU behind him. Two years later, in the capital city of Limpopo province in the north of South Africa, and five days before Christmas, Zuma dethroned Mbeki as ANC president.

This began a nightmare of looting of state resources, and the demolition of the Mandela vision of a united country. The destruction continued throughout the Zuma years and, sadly, was not halted during the first four-year tenure of Cyril Ramaphosa, Zuma’s successor.

Today, 18 July 2024, Nelson Mandela would have turned 106 years old. The United Nations declared this day as International Nelson Mandela Day. In a blatant attempt to milk the Mandela legacy and rally the divided nation behind his recently-formed multi-racial Government of National Unity, President Cyril Ramaphosa chose this day to open the seventh South African Parliament.

President Ramaphosa has an unenviable task leading the country forward. The buoyancy that was so palpable during the Mandela era has been replaced with wide-spread cynicism about the ANC, swathes of unemployed people, violence, and crumbling government services. As Zuma’s Deputy President during the years known as the state capture period, Ramaphosa suffers from a compromised and tarnished reputation. It is imperative that he and his party remember what we as a nation lost when they started trampling on what Mandela bequeathed to South Africa.

My stint as a parliamentary television reporter for the South African Broadcasting Corporation included part of what I would call South Africa’s Camelot years under then President Mandela. Some of the memories of those years are cloaked in gold and remind one of what can be possible if there is not a chasm between leaders of state and their people.

The South African Parliament was not as security conscious then as it is today. Schoolchildren would stand outside a Parliamentary fence and entrance in Plein Street and in the Company’s Gardens, from where they had a view of the presidential gardens and could see the President if he took a walk. When the young people saw President Mandela, they cheered him and shouted his name. He would slowly head in their direction to greet them.

I was a witness to this in April 1995. President Mandela received the Tunisian President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. As they were walking in the beautiful garden, a group of excited schoolchildren called out to Mandela. He looked at them, smiled that huge world-famous smile, stopped briefly, and told his guest: “Excuse me, Mr President, I must greet the children.”

It was a gobsmacking day. A president interrupted his walk to wander over to greet children, reaching out to shake some hands and giving them memories that they would cherish forever. It’s quite likely that President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali would also ponder about this for years: an African president not surrounded by a phalanx of guards, ambling over to adoring youngsters.

In 1998, I was working as Deputy Editor of Pretoria News in South Africa’s capital Pretoria. One day in March, President Mandela paid a goodwill visit to our offices. He caused mayhem as work stopped and all my colleagues wanted to have a picture taken with him. Outside the building, people gathered to catch sight of him. One of them was my then doctor, Suna Moller.

Weeks later she told me how one Sunday morning she and her family were travelling by car on the N1, the national road that starts in Cape Town and runs to South Africa’s Beit Bridge border with Zimbabwe. She noticed what she thought was Nelson Mandela’s official vehicle ahead. She asked her disbelieving husband to drive next to the President’s car and at the same time urged their children to wave at the passenger. They did. Slowly a window of the vehicle next to them was lowered. A smiling face and a waving hand appeared. It was Nelson Mandela.

While in prison, Nelson Mandela lost a son and his mother and was not allowed to attend their funerals. He grieved deeply and from the support and empathy from fellow prisoners that buttressed him then, knew how important it was to reach out in times of bereavement.

He was out of office when his friend and former jailer Christo Brand’s son died in a motor vehicle accident. Brand had just identified his son’s body and was driving home with a relative when his cellular phone buzzed with an incoming international call. It was former President Mandela. He was calling from a neighbouring country (Mozambique) to sympathise with his friend and to share with him that children should be burying their parents and not the other way around.

Loyal to his friends, Mandela was fond of Brand. He was not alive when Brand launched his memoir, Doing Life with Mandela: My Prisoner, My Friend, in London. He was surprised when he noticed Mandela’s daughter Zindzi at the book launch. Her presence, she explained to the surprised Brand, was because her father had prevailed upon her to be there.

These vignettes are but small harbingers of the legacy of Nelson Mandela and sadly show what South Africa has lost since Mandela left office. While Thabo Mbeki could still, in a way, steward the Mandela legacy, things fell apart after him. Jacob Zuma was a disaster, and Cyril Ramaphosa was Jacob Zuma’s loyal Deputy President throughout those calamitous years. Although he has damned the Zuma era as lost years, he was part of it.

Opening Parliament on Nelson Mandela’s birthday just pays lip-service to the immense legacy of Mandela. As the leader of South Africa, President Cyril Ramaphosa must walk rather than talk reconciliation. His task is huge. Mandela was a towering international figure who commanded universal respect. Ramaphosa still has four more years to redeem himself. South Africa needs him to rise above himself and rekindle the vision with which Nelson Mandela inspired the whole world.

Dennis Cruywagen is an acclaimed South African journalist and political commentator, as well as a former parliamentary spokesperson for the ANC. He previously served as deputy editor of the Pretoria News and a political reporter on the Cape Argus. He is a recipient of a Nieman Fellowship and a Mason Fellowship at Harvard University, and holds a master's degree from Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. He is also the author of Brothers in War and Peace and The Spiritual Mandela: Faith and Religion in the Life of Nelson Mandela.