A report published by Christian Aid and its partners has revealed that more than half of African countries are spending a significant amount of their budgets on servicing debt at the expense of critical funding to sectors such as education, healthcare and infrastructure.

The report titled Between Life and Debt reveals that African countries paid $85 billion in debt repayment to external creditors in 2023, the highest since 1998. It sourced the data from the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics database. The repayments are expected to rise higher in 2024, with African governments setting aside $104 billion in their budgets for external debt service.

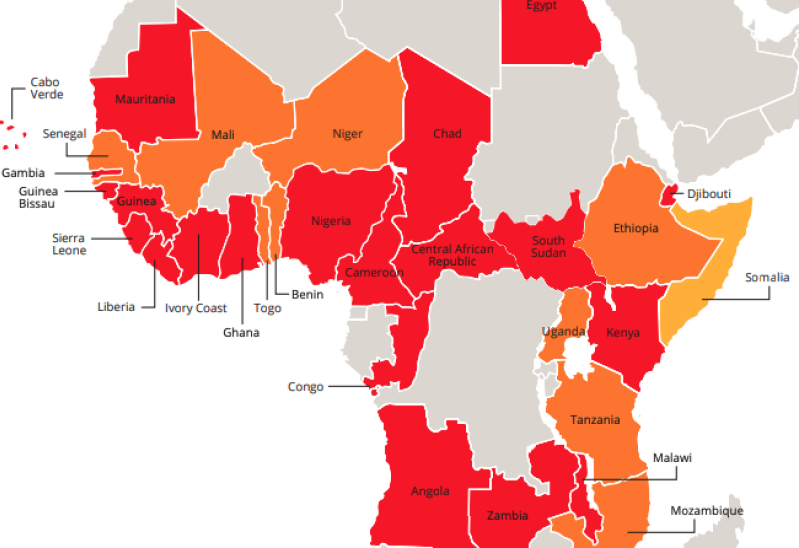

The report examined the debt crisis in Africa using five countries – Kenya, Ethiopia, Zambia, Nigeria and Malawi – as examples. Four out of the five featured countries are part of the 23 countries in Africa that spent more on repaying external debt than on education and healthcare. Ethiopia and eight other countries spent more on external debt than healthcare but not on education.

Former UK Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, termed Africa’s debt crisis an “injustice” perpetuated by an interconnected economic system that has failed the global majority.

“Christian teaching tells us that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice anywhere. The scale of this inequality between Africans and the rest of the world is so great that I am not sure the world will ever forgive us for failing to deliver urgent debt restructuring,” said the former PM in the report’s foreword.

For context, African governments' external debt payments will average at least 18.5% of budget revenues in 2024. This is a precarious position according to the IMF data, which shows governments struggle to repay external debts once they are higher than 14% of revenue.

The composition of the debt has also contributed to shrinking spending on critical services such as hiring more medical personnel, equipping hospitals, recruiting teachers and mitigating climate change challenges. Fourty-six percent of external debt payments goes to private lenders who charge higher interest rates averaging 6% and above while Chinese lenders, multilateral and bilateral lenders charge 3%, 1% and 1.3% respectively.

In Kenya, for instance, public spending per person has fallen sharply from 2017 as debt repayments have increased. The country is using 24% of its revenue to service debts, half of which is from expensive private lenders. The National Taxpayers Association (NTA), a partner of Christian Aid, has raised the alarm over the lack of medicines and specialized equipment in most public hospitals.

“There have been delays in government disbursements of capitations to schools as well as payments for social protection transfers and public world programmes adequate resources to sustain social services,” reports the NTA.

In neighboring Ethiopia, the government defaulted on a $1 billion foreign currency bond in December 2023 following mixed efforts to restructure or cancel loans owed to private lenders, multilateral and Chinese creditors. The government is not able to pay the salaries of healthcare professionals and school teachers as a result of the debt squeeze.

Even in the oil-rich country Nigeria, a series of external shocks such as the drop of international crude oil in 2018 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has led to a spike in debt. Nigeria’s private external debts are already at very high interest rates, averaging over 7%, notes Christian Aid.

Munachi Ugochukwu is the Senior Program Officer at the Abuja-based Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre. He said that Nigeria’s increasing public debt, persistent inflation as well as its rising cost of living pose serious risks to the country’s economic growth.

“With the debt crisis, most of the country’s revenues are now being channeled to debt servicing obligations at the expense of basic social services, commitments on gender equality and the promotion of women’s rights, and other development exigencies,” commented Ugochukwu.

Infrastructure needs lead to risky debt

Speaking to Christian Daily International, Financial Analyst Chipo Muwowo traced the debt crisis to capital demands required to finance infrastructure development. Referencing figures from the Africa Development Bank, Muwowo said the continent needs between $130 and $170 billion annually for infrastructure development.

“To invest in this, African governments have to borrow often from international markets. One of the major challenges, however, is that African governments borrow in US dollars while the income being generated from their infrastructure investments is most likely to be generated in their local currency. Repayments become very expensive if the respective local currency loses significant value against the US dollar in the intervening years,” said Muwowo.

The knock-on effect, added Muwowo, is the redistribution of national income away from social services and towards debt servicing.

Christian Aid paints a picture of this redistribution in Zambia where the government cut public spending on healthcare by 13% between 2014 and 2022 while spending per person on education fell by a staggering 40% at the same time to accommodate debt repayments which had ballooned to 24% of the government revenue.

“In the case of Zambia, President Hakainde Hichilema has spent the bulk of his first term renegotiating Zambia's international debt obligations following the country's default during the COVID years. In addition, it introduces volatility to markets. Currency fluctuation becomes the norm which, in many African contexts, leads to inflation because many of our countries are net importers. Higher inflation makes life more expensive for households which means many can't afford enough food,” said Muwowo.

Rethinking and addressing the debt crisis

The call to rethink and address the debt crisis in the global south should be a concern for both the lenders and borrowing nations, said Christian Aid’s Senior Theology Advisor Bob Kikuyu.

“A moral assessment of debt policies must include the extent to which the debt burden undermines the ability of governments to fulfill their obligation to promote the common good, forcing them to spend their scarce resources on servicing debt, rather than on human capital investments,” commented Kikuyu after the release of the report.

Christian Aid pointed out that previous attempts to address the debt crisis have been inadequate and have been complicated by recent global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and rising climate change risks. The partner organisations that compiled the report advocate for a debt cancellation mechanism anchored on an UN-led framework for debt resolution. This would prioritize development goals and compel private lenders to participate in debt relief measures.

The UK-based Christian organisation has also challenged the government to acknowledge its moral and historic responsibility to help address this problem and build a debt system that delivers real relief.

“The UK has outsized influence within its own jurisdiction and in many global forums, such as the UN Security Council and the World Bank and IMF. That means the UK Government has the power to act at a national and global level right now.”